Introduction

Rheology is the science of flow and

deformation

of matter and describes the interrelation between force, deformation

and

time. The term comes from Greek rheos meaning to flow. Rheology is

applicable

to all materials, from gases to solids.

The science of rheology is only about

70 years of age. It was founded by two scientists meeting in the late

'20s

and finding out having the same need for describing fluid flow

properties.

The scientists were Professor Marcus Reiner and Professor Eugene

Bingham.

The Greek philosopher Heraclitus described

rheology as panta rei - everything flows. Translated into rheological

terms

by Marcus Reiner this means everything will flow if you just wait long

enough.

Fluid rheology is used to describe the

consistency of different products, normally by the two components

viscosity

and elasticity. By viscosity is usually meant resistance to flow or

thickness

and by elasticity usually stickiness or structure.

Classification of materials

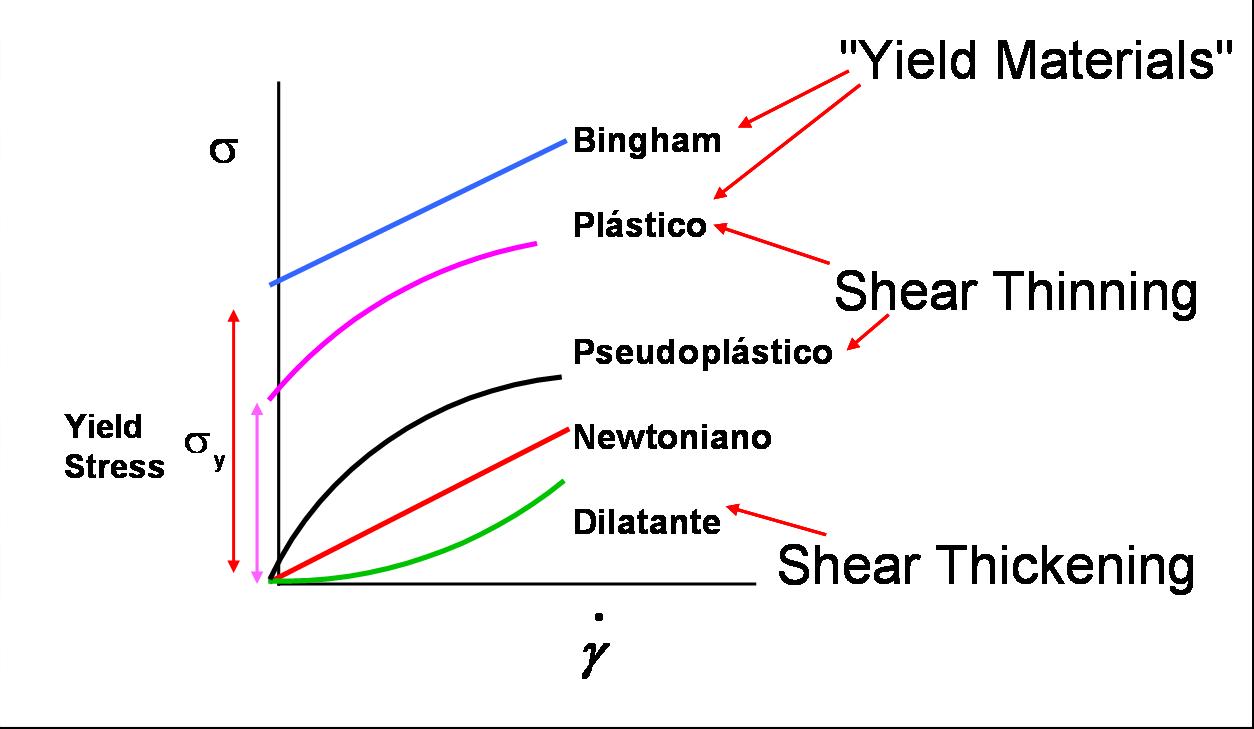

Fluids are normally divided into three

different groups according to their flow behaviour:

Newtonian fluids

Non-Newtonian fluids, time independent

Non-newtonian fluids, time dependent

Flow curves

Kinematic and dynamic viscosity

Kinematic viscosity is measured with

kinematic

instruments , normally different types of cups which means that the

knowledge

and control of shear rates is limited or non-existent. Therefore

kinematic

viscosity values are of little or no use for design of equipment for

non-Newtonian

fluids.

Dynamic viscosity takes into account the

effect of shear rate and time and is therefore the only type of

viscosity

relevant for non-Newtonian design purposes. Dynamic viscosity is

measured

with dynamic instruments, either rotating (shearing) or oscillating.

An instrument only capable of measuring

shearing viscosities is called a viscometer and the oscillating type is

called a rheometer.

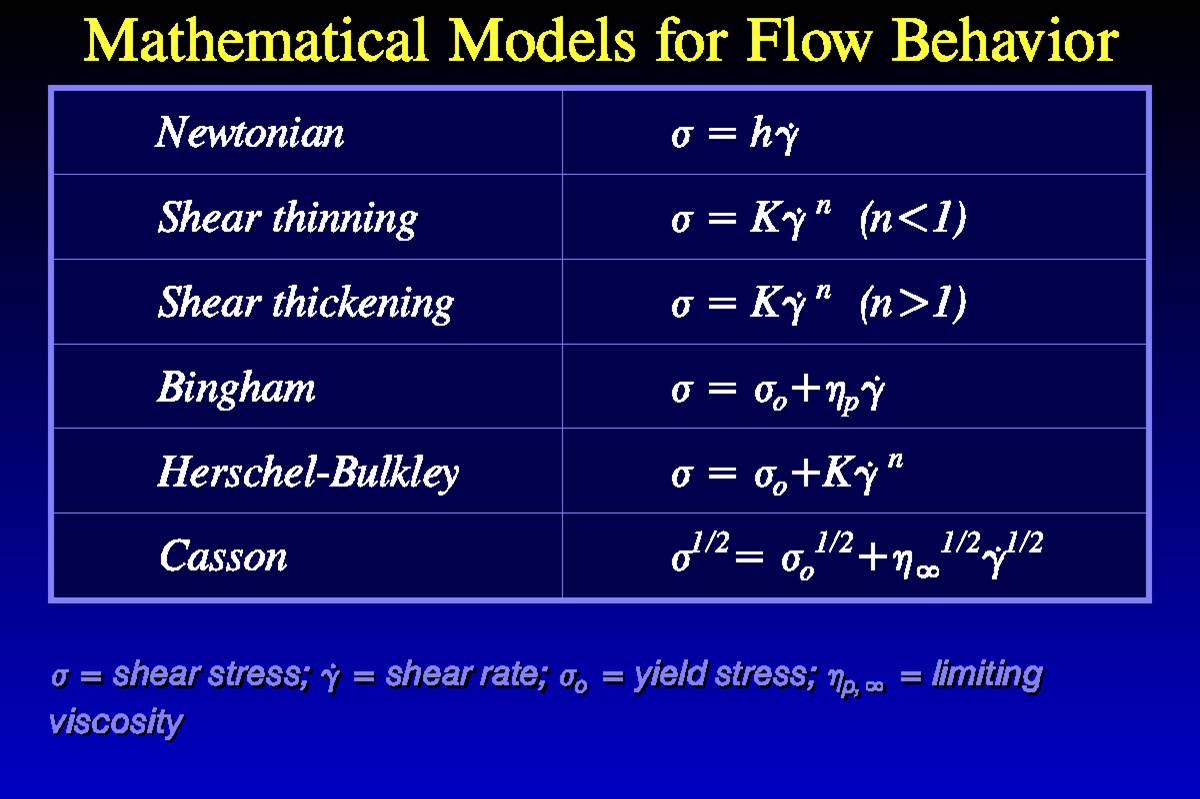

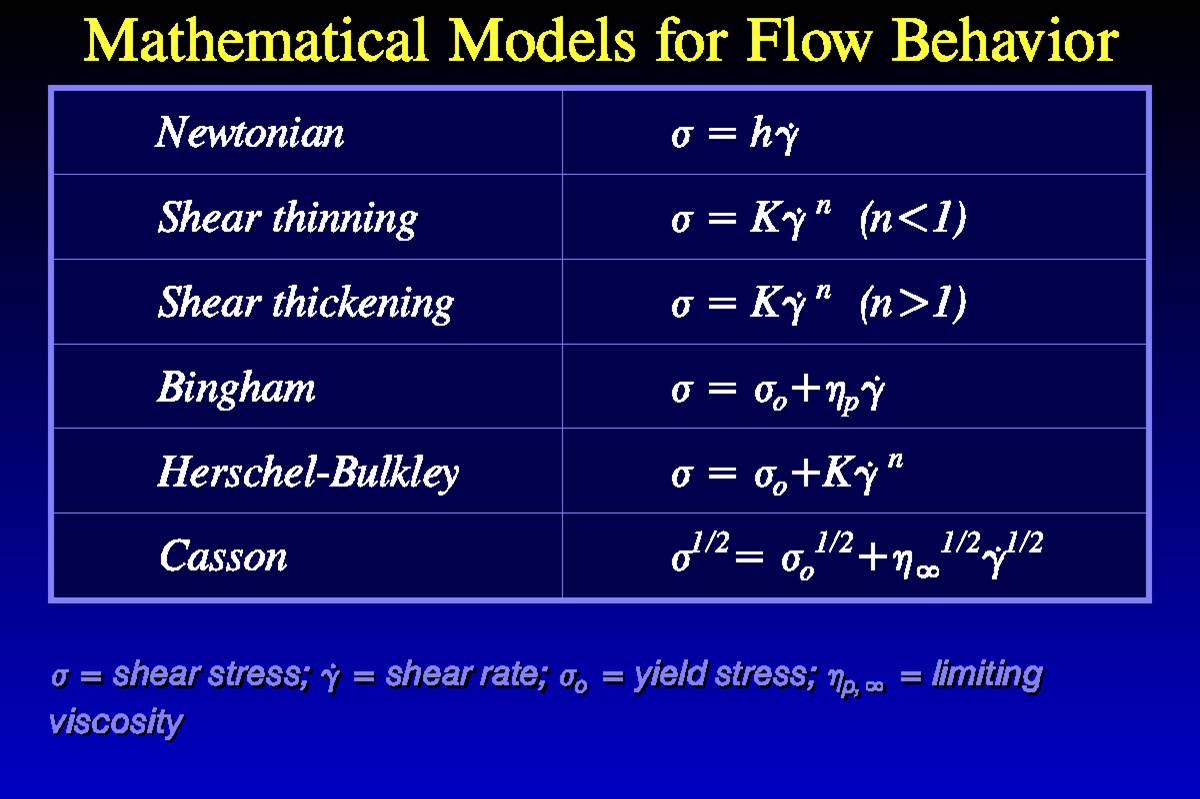

Basic constitutive equations

Various models for approximation of

rheological

data have been presented. One of the most widely spread models is the

so-called

power law for approximation of viscosity data. The main reason for the

power law being so popular is that the shearing rheological behaviour

of

a fluid is represented simply by a straight line in a log-log shear

rate/shear

stress graph. Another reason is that the shearing behaviour of most

fluids

lends itself to a good approximation applying the power law.

Viscoelasticity

All materials, from gases to solids,

can

be divided into the following three categories of rheological behaviour:

Viscous materials: in a purely viscous

material all energy added is dissipated into heat

Elastic materials: in a purely elastic

material all energy added is stored in the material

Viscoelastic materials: a viscoelastic

material exhibits viscous as well as viscoelastic behaviour

Typical examples of viscoelastic

materials

are bread dough, polymer melts and artificial or natural gels.

Note: in the rheological sense water is

a "viscous" fluid. Normally, however, the term "viscous" is used for

fluids

with high viscosity.

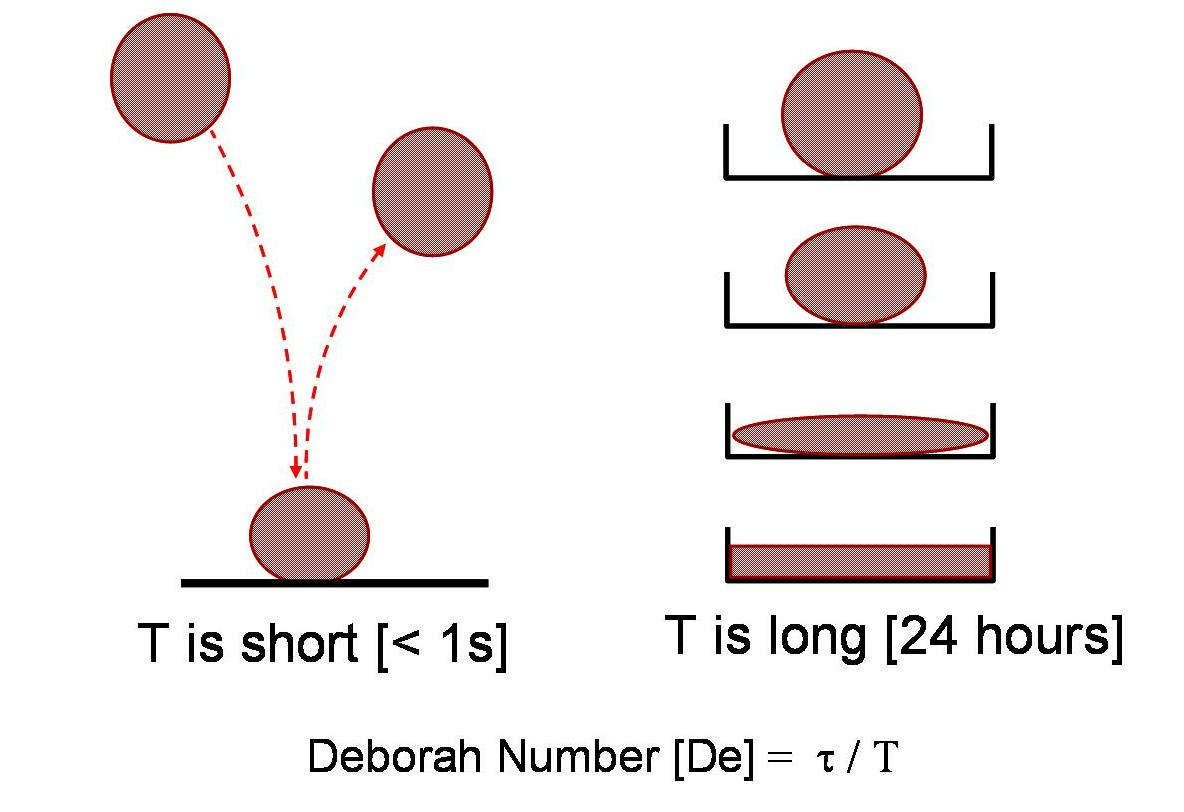

In most cases of viscoelastic behaviour

the time factor has a significant impact on the flow properties

observed.

A measure of the influence of time is the so-called Deborah Number, D:

D = (response time) / (observation time)

An example of a system having a large

Deborah Number is a normal glass window. If old enough, e.g. an old

church

window, a difference in thickness at the top and at the bottom can be

easily

measured. Although the viscosity of glass is high, about 1040 Pas, it

is

still a liquid and consequently it flows. However, the observation time

has to be long, perhaps a couple of centuries, to observe the movement.

When shearing a viscoelastic fluid

so-called

normal stresses will appear. These normal stresses can result in flow

behaviour

quite different from that of Newtonian fluids.

Viscosity and elasticity measurements

Rheological measurements are normally

performed

in kinematic instruments in order to get quantitative results useful

for

design and development of products and process equipment. For design of

products, e.g. in the food, cosmetic or paint industry, rheometric

measurements

are often performed to establish the elastic properties, such as gel

strength

and yield value, both important parameters affecting e.g. particle

carrying

ability and spreadability. For design of process equipment the

properties

during shearing of the product is of prime interest. Those properties

are

established in a normal viscosity measurement.

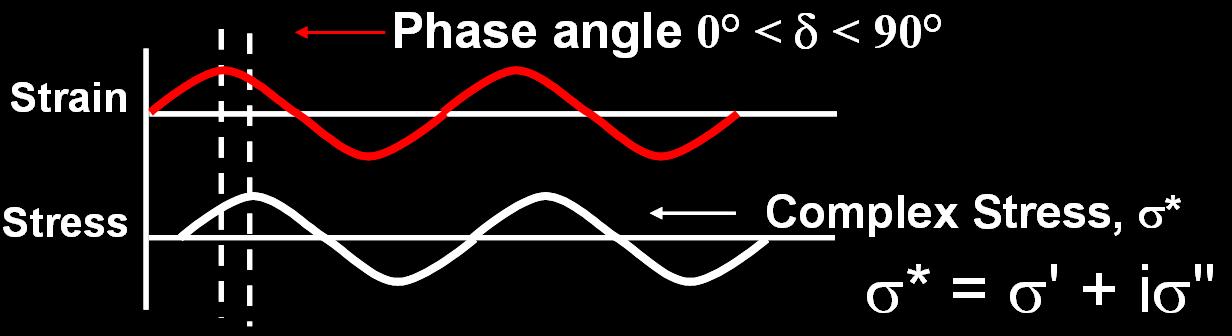

A rheometric measurement normally consists

of a strain (deformation) or a stress analysis at a constant frequency

(normally 1 Hz) combined with a frequency analysis, e.g. between 0.1

and

100 Hz. The strain sweep gives information of the elastic modulus G',

the

viscous modulus G'' and the phase angle d. A large value of G ' in

comparison

of G '' indicates pronounced elastic (gel) properties of the product

being

analysed. For such a product the phase angle is also small, e.g.

20º

(a phase angle of 0º means a perfectly elastic material and a

phase

angle of 90º means a perfectly viscous material). The frequency

sweep

gives information about the gel strength where a large slope of the G '

curve indicates low strength and a small slope indicates high strength.

A viscometric measurement normally

consists

of a shear rate analysis. The shear rate sweep should preferably cover

the range applied in the intended equipment. For liquid foods a shear

rate

range from around 1 to 1,000 s-1 covers the needs for a low-viscous

product,

e.g. milk or juice, and a shear rate range from around 1 to 100s-1

covers

the needs for a high-viscous product, e.g. tomato paste or quark.

Below a number of examples from

measurements

on some fermented dairy products are found. The fermented cream has a

fat

content of about 35%, the fermented milk "type 1" has a fat content of

0.5% and the fermented milk "type 2" has a fat content of 1.5%. Note

that

despite the difference in the elastic modulus G ' between the two

fermented

milk types being significant, the viscosity curves are nearly

identical.

The practical implication of this is that when the two products are

sitting

in a cup the "type 2" fermented milk seems to have appreciably higher

viscosity

than the "type 1" milk, but when subjected to shear, e.g. when being

pumped

through a pipe, the pressure drop will be much the same for both

products.

What is observed in the "cup analysis" is instead the more pronounced

elastic

properties of the "type 2" milk giving the impression of a higher

viscosity.

For the youghurt a significant degree

of thixotropy can be seen in that the "up curve", i.e. the curve

obtained

when increasing the shear rate from zero and upwards, is appearing

above

the "down curve", i.e. the curve obtained when going back in shear rate

to zero. For comparison of the degree of thixotropic behaviour the

distance

or area between the two curves can be calculated, applied to either the

shear stress curves or the apparent viscosity curves.

Read more at the rheology page by Prof

Ulf Bolmstedt

| Back |